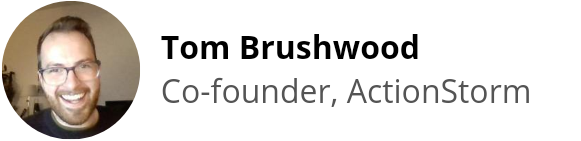

There’s more to campaigning than you think – most of it happens behind the scenes, away from computer screens and press headlines. From identifying the problem, to meeting the decision makers, let’s talk about how to get that meaningful result.

Ok, so you want to change the world.

First of all, that’s great news – it’s good to have you here – we need all the people we can get. Welcome to the wonderful, weird world of campaigning.

We all know what a petition looks like – but so much of what happens in campaigning happens behind the scenes.

So how does a campaigner go from petition to achieving a meaningful impact? What happens before the petition is even conceived?

It’s time to make the invisible, visible. In this article, we’ll go behind the scenes and explore how change really happens.

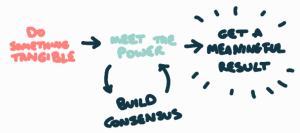

First things first. What kind of change are you trying to create?

There are several types of problems that great campaigns are sprung from. Generally, they fit into one of a few different categories –

- A legal problem – i.e. seeking to change a law

- An enforcement problem – i.e. upholding an existing law

- A social problem – tackling anti-sociable policy or behaviour from another person (something that isn’t breaking a law, but is anti-sociable or unkind)

- A policy problem – a public body or organisation with a policy that is wrong, unjust or ineffective and convincing them to change priorities or budgets

A surprising amount of problems are actually a problem of enforcement. Police forces have limited budget and resources to enforce the law, and more violent crimes are (rightly) prioritised over lower level crimes. Plaintiffs also often have limited ability or resources to take those who break the law to court.

If you think you’re seeking a change to the law, you may be wise to check that the real problem isn’t really a matter of enforcement. If it is, often that’s due to a lack of real evidence, inability to collect the evidence, or an inability to prosecute the offenders in court.

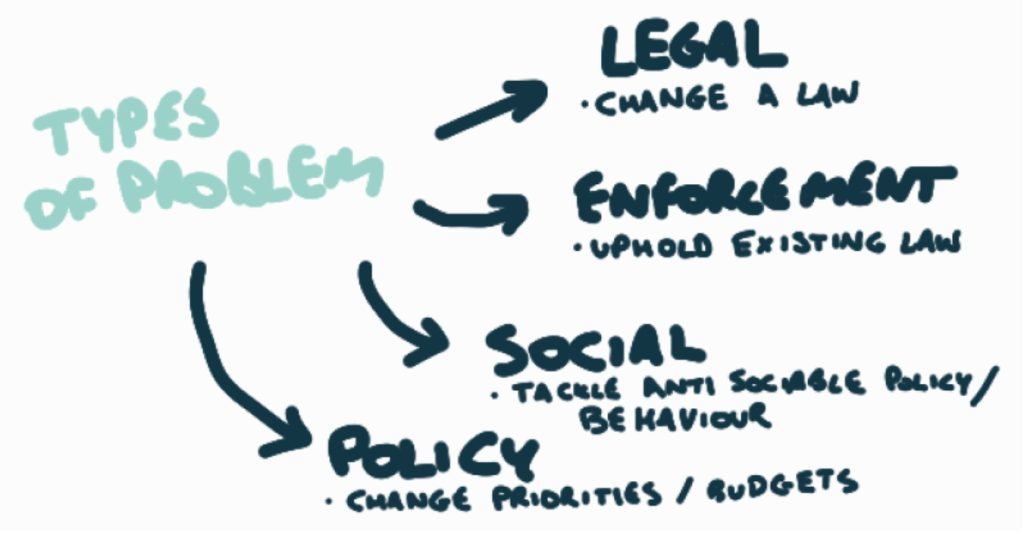

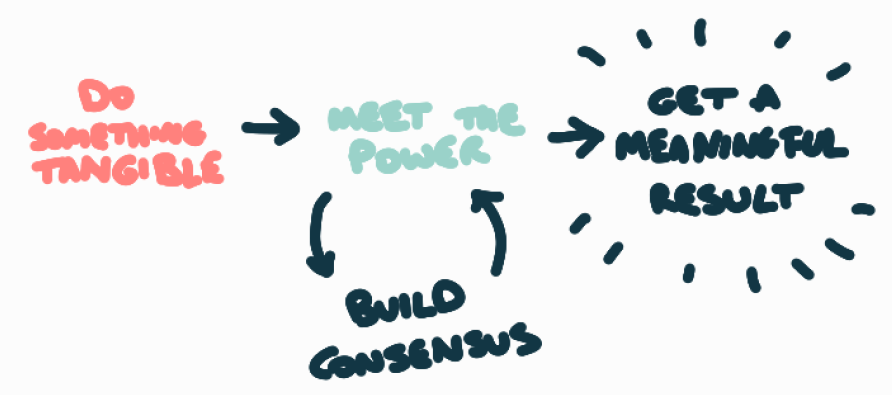

Change is messy, and doesn’t all happen in a linear process, but if it did, it might look a bit like this.

Step 1. Map out the real problem

The most obvious place to start is the effects or problems you’re witnessing on the surface. But there’s probably more to the problem than that. What’s causing the effects you’re seeing? Try and map it out on a piece of paper.

As an example, let’s say that sewage is being discharged into your local river, and as a result, wildlife is being affected, local residents are unable to swim in the river and there are wild algal blooms suffocating the plants and fish in the river.

You might start by asking yourself, who’s discharging the sewage? Is it just one company or are there several? Are the discharges happening in a single location or in many?

What’s the real problem – is it illegal for the company to do it? If so, it’s an enforcement problem. If not, is it just a bad policy on the part of the company? Are there other options available to the company to deal with the sewage? If so, why are they choosing to dump it – is it cheaper?

At this point, it would help to do some of your own research on the matter – you’ll be surprised how much of this you’ll be easily able to find online. And once you’ve done that, you might feel comfortable enough to approach someone who’s a subject matter expert.

Step 2. Get real evidence

At this point, once you’ve done a little bit of research into the underlying problems or causes behind the issue, it’s time to start collecting real evidence.

The type of evidence you might be looking for will change based on the campaign, but it will include some kind of proof of wrongdoing – whether that is evidence-based (like soil samples), story-based (collecting stories from those affected) or legal-based (local laws, government policy, company policy).

You don’t necessarily have to collect this evidence yourself. Someone might have already done the hard work – evidence might be freely accessible online (data samples, freedom of information requests, and so on). Or you might want to ask others to help you collect evidence and stories that will help you build the case for change.

In our river sewage example, collecting water samples from different locations on the river might prove that a certain facility, owned by a certain organisation, was responsible for 90% of the pollution in a river.

Walking the full length and breadth of a river to collect water samples yourself sound like a good workout, but it would be a bad use of time when there are so many people who care about river quality and sanitation. Why not start a local pressure group and ask them to help you collect the samples needed so you can stop the sewage dumps once and for all?

Step 3. Make it visual and tell the story

Human beings are social, visual creatures and we communicate primarily through story and image. You’ve got to make what you’ve seen understandable and relatable to others in order to build support, and persuade others to act.

Illustration. Audio. Diagrams. Video. Whatever helps you get the message across.

You’ve understood the problem. You’ve collected the evidence. Now you need to show it off.

A good story will make three types of connection with its audience – a personal connection (understanding who is affected and why it matters to them), an emotional connection (understanding why this is important and why we need to act now), and a rational connection (understanding the facts behind the stories)

In the river example, we could make a map showing where sewage is being dumped, and which are the companies responsible. We could put this map up around the local area, send it to our MP, to the company, or even to the employees of the company. Whoever you think you could convince to stand up and be counted as part of the public pressure.

Build support throughout these stages

All of these early stages are good moments to build public support and find allies along the way. Residents. Local leaders. Experts. Journalists. Politicians. Anyone and everyone willing to help.

People power. At this stage, all allies are valuable – and you’re certainly going to need them later on.

Step 4. Now it’s time to do something tangible.

In other words, time to make your move, and build the pressure on the decision makers.

What you decide to do could fall into a few different categories – it could be local pressure (for example on council members or MPs), legal pressure (mounting a legal challenge through the courts), public pressure (including press – naming and shaming those responsible), or national pressure (through public institutions, complaints to regulators, unions, and so on).

For best effect, you should escalate your actions over time. For example, a small press reveal, followed by a bigger press reveal a few days later. The illusion of momentum is important – it makes it hard for decision makers to ignore the issue. Make them think this story isn’t going away any time soon.

The most impactful action you could do depends on what you’re trying to achieve. Often, the uniqueness, novelty and shock value of your action is part of the punch. Generally as more groups use the same type of action, the action carries less weight. The first email a decision maker reads about a topic will carry a lot more weight than the 100th email they read about it.

If you’re lucky, those in charge will have no other option but to reluctantly accept your invitation to discuss the issue face-to-face.

Step 5. Now you have the attention of the decision makers, it’s time to ‘meet the power’.

If the result you’re after is a change in policy, for the best results, you must now meet the decision maker face-to-face.

So far, you’ve probably approached the early stages of campaigning with some level of aggression and hostility towards those in the wrong, but if those same people are the decision makers, your campaign will not go much further without a change of attitude. At this point, you should approach the negotiation table with understanding and grace, not hostility.

Generally, the difficulty at this stage is finding a solution which is amenable to all parties. For every new policy, there are winners and losers. But a wise campaigner will try to find a win-win solution. Most issues boil down to money, usually.

If you’re working with MPs, you’ve got to give MPs an escape route. You’ve got to understand all viewpoints, all parties involved – you’ve got to present them with a solution that makes everyone happy.

If the result you’re after is about enforcement of an existing law, the evidence you’re able to collect will be your biggest friend. The police are often amenable to working with pressure groups who can collect the evidence for them, saving them precious time. Don’t be scared to reach out to a local branch to try and start a conversation.

If the result you’re after is a change in law, aside from generating public pressure, you’re best off seeking legal counsel on what happens next. Your first step should be to seek a legal opinion, and you can go from there.

Ultimately, your job is to build consensus with the decision makers, and give them a path forward that will get the result you’re looking for, and keep everyone happy in the process.

The golden rule, as one of our campaigners puts it, is to “be a pleasantly persistent pain in the arse.”